The following post is a transcript of a 1967 Bobby Darin interview that, it’s fair to say, is the most in-depth that we have yet come across. The audio was found in a corner of the internet by Alex Bird (and if you haven’t heard his own albums, check them out now!). Running for half an hour or so, much of it was distorted or playing at the wrong speed. Alex got everything running at the right speed, and then did a transcription of the interview. That was then passed to me, and I have edited it and added notes. Matt Forbes (and if you haven’t heard HIS albums, then you should check them out, too!) also helped with this process over the last few weeks.

In the interview, Bobby chats about his own recording career, what he thinks of the music scene at the time of the interview, and also tells us about the times when he was working as a demo singer – filling in a period of time in his early career that we knew nothing about. I have edited the interview, but made very few changes of note. I’ve removed repetitions etc, and also short sections that, for one reason or another, don’t make much sense (often because the audio was missing). In short, I’ve tried to make it work as piece of text rather than a piece of audio. Sections in bold are notes added by myself. Sections in blue are spoken by the interviewer, although I have tried my best to make this read more like an article than an interview, but that wasn’t always possible.

We hope you enjoy this rare and very revealing interview. The original audio is linked to at the bottom of the post.

*

“It’s Got to Be Right:” Bobby Darin discusses his music career. (1967)

The Writing and Recording Process

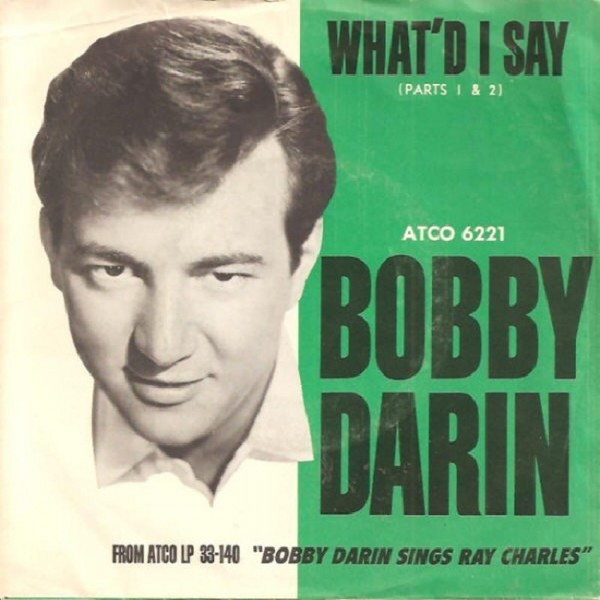

In 1958, I sit down and write a song called Splish Splash, which is a novelty song with rhythm and blues chords and a simplistic approach piano wise – because I’m writing songs at the piano trying to use both hands. Now, it becomes a hit record and, the next thing I know, there’s a typification program happening. Then we come with Queen of the Hop, which is more or less in a similar bag. It’s got more of a New Orleans kind of flavor to it. And Early in the Morning is a real gospel, I Got a Woman kind of changes. And, of course, I Got a Woman is a derivation from church – the gospel rolling piano that Ray Charles was so famous for, along with slews of people who never made the pop scene.

Soon after, I get into what I liked to call at that time “a pretty chord sequence,” like, Dream Lover. Again, to me, it requires a different sound. First of all, I don’t have the same vocal placement. When I hear a certain kind of thing, when I go into a country bag, I’m into a country bag and it becomes a vocal placement. I couldn’t sing a country and western tune in the same approach that I would sing a pop standard ballad and/or a rhythm & blues tune. So, what I don’t realize at the time is all of it’s coming out at once and I’m trying to place it. I’m as guilty of the thing I resent most, which is categorization, but I can’t control it.

We dissolve and it’s 1964 or 1965, when I find myself in this position that I’m starting to force things. I’m trying to overlap, and place into specific bags, individual things that I’m doing. All of a sudden, it’s 1967, and I just have to do what I feel, as I feel it. So, I go in and I do a Dr. Doolittle, which I feel in a certain way.

[Right] now, I’m in the process of putting together an album of what I call potpourri. There’s some rhythm and blues things in there, some country-oriented things, some bluegrass-oriented things, because I feel those things. And I’m doing them now for me. Again, I’m back into recording what I really dig and groove behind. Whether they are commercial successes, well, that’s a later factor. I would like them to be – no artist wants to go in and have a bomb – but that’s not a significant factor.

[Note by Shane Brown: The sessions that Bobby is talking about here were taking place in late 1967. The rhythm ‘n’ blues numbers he mentions are probably Easy Rider and Everywhere I Go, first issued on the Rhino boxed set in the 1990s. The country track is likely to refer to the likes of Tupelo, Mississippi Flash (unreleased), as well as I’m Going to Love You and Long Time Movin’, both of which straddle the country and folk genres, and both were, again, released on the 1995 Rhino box. The bluegrass song is Honey, Take a Whiff on Me. Many fans will be aware of Bobby’s performance of this on a 1969 TV special, but, until recently, there was no record of a studio version being made. However, we now know that the song was taped in the studio in 1967. It remains unreleased. It’s worth adding that Easy Rider, Everywhere I Go, I’m Going to Love You, and Long Time Movin’ were referred to as demo recordings when first released. This 1967 interview corrects that, with Bobby confirming these sessions were intended for an album project. Documentation seen recently also confirms that these were regular studio recordings.]

I used to try to plot what an audience wanted to hear. I don’t mean this to sound like a professional and a penance session, but, by the same token, these are facts that I’m expressing. You put me into a studio with five guys who are really nitty gritty funky blues players, and that’s where I go. That’s where I am. You put me into a Nashville studio with guys who have got that twang, [and] that’s where I go. You put me into a studio with 35 lush strings, and that’s where I go. So, the music really dictates to me rather than me dictating to the music. I can just say that it happens on an emotional level. It happens to me. I know I respond to it, and I know that people there respond to it. And I’m hoping now that what happens is I go in and I have that freedom, which is something that I’ve always had. Nobody’s ever squashed it, nobody’s ever tried to put it away, but, by the same token, I did it to myself. I started over-listening instead of doing.

We’re going in on Thursday to record a couple of tracks. We may not get them Thursday, [so] we’ll come back on Monday. That’s the thing I could never do before, and now I can. I couldn’t understand how it would take so long to do one or two tracks. Well look, the chemistry’s not working today. It’s Thursday [and] it’s rainy…the car broke down, the market’s off…I’ve got a headache. Instead of trying to account for all those factors, make them work for you. If they don’t work for you, just stop, go back, and do it again. Do it until it’s right. That’s really where it’s at. There’s nothing now that will ever come out that’s not right. Now I’ll stand behind it.

[Note by Shane Brown: What Bobby is saying here about not previously going into the studio to re-do songs he wasn’t happy with isn’t actually true. There are many occasions where Bobby was unhappy with his first attempt at a song, and so went back into the studio at a later date to try again. His willingness to do this goes back as far as the late 1950s and continued through the Capitol years and beyond.]

It started with the Carpenter album, there is nothing on that album that I won’t stand behind, nothing on the Inside Out album that I will not stand behind, nothing on the Dolittle album that I won’t stand behind. On the new project [there’s] a couple a things we don’t like. We hear them back and say the track is wrong, and the song is not for me. We just put a pass on those things that aren’t right, because my needs have changed. It’s got to be right. Now, if it sinks or if it swims, fine. But at least it’s right going out.

Bobby as Songwriter Demo Singer

I earned my living, for about a year and a half, recording songs for the artist to sing. I was a demo record singer in New York City, and you would get 10 or 15 bucks a side, depending on the publisher involved, or whether you knew the writer etc. And he would say “Now look. I got a song for Perry Como”. And he would give me the tune, and I’d learn it. We’d go in with a trio or quartet, and I’d sing “Catch a falling star and put it in your pocket, never let it fade away.” Or “we got a song for Presley” (Bobby does Elvis Presley impression). Having that vocal flexibility, I was able to sometimes earn $100 dollars a week – just going in and singing songs that were going to be put onto acetates and mailed out to other artists. And nobody ever asked who it was singing

[Note by Shane Brown: This is new information. When looking through magazines and newspapers from 1956, Bobby seems to just disappear for about nine months or so from the late summer of 1956, reappearing again in the spring of 1957. He doesn’t appear to have been doing commercial recording sessions, TV work, or live appearances. Bearing in mind that he references Catch a Falling Star and Elvis here, it is almost certain that Bobby is talking about that “lost” period. It is known that some demo records by Bobby from the mid-1950s are still in existence, but the titles are unknown, and they haven’t been heard by the editors of this interview transcript.]

As I say, the demo record business was quite a lucrative thing for me. And it was never for professional or commercial use, merely to present [the song] to the A&R man or the artist himself. It’s a great experience, certainly, because so many times I had I had a chance to get before a microphone in the studio before I was up to bat as Bobby Darin. So, it kinda worked.

[Note by Shane Brown: This would explain how and why Bobby’s recording and singing technique improved so much between the Decca recordings and the May 1957 sessions which ultimately led to his ATCO contract.]

Bobby on Influences and Writing

People that you really are strong for cannot help but influence you. I’m as influenced by Ray Charles and by a Frank Sinatra as I am by an Al Jolson, for that matter, or a Bing Crosby, because those people have made contributions. There’s no question about it that there’s some degree of innovation involved. Now, I think, that there is little left to innovate but the little that is left is what I’m after. I don’t know that anybody can consciously do it, I think you can sit with all the maps, all the records, all the charts in the world and try to…and it doesn’t happen.

You take Ray Charles, a classic case in point. Ray was an underground artist for a long time. I go back with Ray Charles in terms of being a fan to when he sounded like Nat Cole. Some people might stand up and say, “now, wait, he never sounded like Nat Cole”. I’m telling you he sounded like Nat Cole and worked with a trio and came out of Washington in the [early] days.

Ray was influenced by Nat. Now, all of a sudden, he got into a church kind of thing and now he was starting to do, you know, Ain’t that Enough or What’d I Say or I Got a Woman. Things that were new and fresh – not for the people who would listen to them and heard those things, but for a whole mass who had never heard them. Strangely enough, though, he was never as successful as he was at the moment he had the vision to see that a Hank Williams in his game was doing exactly what Ray was trying to do in his game, in the R‘n’B bag, and fuse the two. So, all of a sudden, he had I Can’t Stop Loving You and You Don’t Know Me. He took a basic Americana source, fused it with another basic Americana source and came up with something which everybody considers new, which, in reality, certainly is not new. There is nothing that is new. But the fusion tended to be, and was, innovative, at least to the degree that it was virtually unheard of in this country.

He was charted. For people to accept a rhythm and blues artist doing “their material” was a huge, huge step. Now, a Sinatra does it in a sophisticated, maybe not as stylized, approach, but [he] takes a song and makes it his own. I think that really determines what I mean by innovative – somebody that takes material and puts it into such a shape and remolds it to such a degree that you exclude it. [With] hundreds of other people, you’re precluded [from] recording that song in any similar fashion at all because the stamp is on it. And Ray does that. Jolson did it. Sinatra does it. Barbara Streisand does it. I think I had an opportunity, and a couple of times did it. I think a song like Mack the Knife and/or Bill Bailey.

Now, it’s more difficult to do it with songs that you do write. Again, you look to the track record [of] Ray Charles [and] the biggest songs he’s had are the songs that he did not write. He had a chance to place something of his own into someone else’s work, a combination factor.

Being a writer, I find that, when I write a tune, the person best suited to sing it is me, because I’ve written it, knowing all my foibles, all my shortcomings, as well as all of the flexibilities, you see? And strangely enough, I’ve had a lot of recordings on songs that I have written, but never a hit with someone else – which implies some sort of weakness in the material. There’s no question about it. Because I write a song like Things and I have a top ten record with it. Dean Martin records it, puts it on an album a couple of years later. It does not step out as a single. And Nancy Sinatra has it out now, but it’s not as a single record. Well, who can figure that? Or You’re the Reason I’m Living. I write it, I sing it, it’s a top three tune and and a lot of people record it, but it’s just placed into an album. So, there’s something generically wrong with my being able to write for other people.By the same token, I think I’m getting closer to being able to write for me as well as do other people’s songs with more of me in them, because the question in the final analysis is “who are you?” You say “I’m me,” but me happens to spread out in more than one or two directions and, therefore, is confusing. I think, for example, that I have let the record player down to some degree when he goes and buys an album in which out of 11 or 12 selections, he does not hear a similarity throughout the 11 or 12 cuts. And he scratches his head and wonders what is going on?

[Note by Shane Brown: His comments here are a bit perplexing, because most of his albums do, in fact, have a coherent style or sound to them. There are very few (outside of compilations of hits and leftovers like Things and Other Things or For Teenagers Only) where he includes country songs and jazz, for example. Sure, he combines country with big band on You’re the Reason I’m Living, but he does that throughout the album, not one style and then the other.]

When you buy Mathis, you buy one sound. When you buy Sinatra, virtually, you buy one sound. When you buy Ray Charles virtually you buy one sound. Well, when you buy BD, you buy a potpourri of things.

Bobby on Being Pigeonholed

I am never bored in a recording studio. I don’t think the people who buy my product are ever bored by the similarity or the sameness of the sound. I’m always experimenting, which is, at points, a hang up, at other points a great advantage. I did an album called Earthy on Capitol, several years ago, which was played for the true folknicks. They asked who it was. Because they dug it. I used natural skin players, the gut string players. The guys who had played those things all their life, the natural pickers. So that the only thing that wasn’t authentic was “Bobby Darin never got on a freight train and he wears a suit and tie.”

I felt bad about that until I realized that’s what they did to Bobby Dylan after he electrified his guitar. So to be good and poor is all right. To be good and successful somehow or other, you’re out, like it or lump it. And I think it’s a shame that that can happen to a Bob Dylan, etc., not that his popularity has waned. I think it’s reached the mass, which is where it belongs. When you’re saying something good. I’m now referring to Bob Dylan and Joan Baez and Judy Collins. And, if being heard by the mass precludes it being an underground art object any longer, well, I’m sorry about that. I was never in any of those categories, so I don’t have to personally feel put down. But, to me, it’s sad that an individual has to be bagged and remain there by any number of his peers. That’s kind of a shame.

Now, what happens is that people come to see a show or performance that I give knowing that they’re going to see a good cross-section of all of the things that have been going on, that I’ve been doing for years. I mean, I used to go out and do Canaan’s Land, an old folk standard spiritual kind of thing, and get 650 out of 1000 rednecks up on their feet with a deafening applause. It got them all together. I do Work Song, which, certainly, it’s got to make you think, since it’s a song about a guy that commits a crime. And they would crack in a nightclub – in that place where you’re supposed to only do songs like My Funny Valentine and I Get Along Without You Very Well, and so forth. And I made them respond to that and I still make them respond to it. And I constantly change the songs involved. But the various approaches can’t change. Otherwise, I could not get up and do the hour and 10 minutes that I do of any one given kind of music. You know, I close with with a medley of Respect, What’d I Say, and Got My Mojo Working. So, I mean, it’s lunacy. And, before that, I’ve done Drown in My Own Tears and Talk to the Animals, Don’t Rain on my Parade and Carpenter.

So, the people who buy albums, I think more or less want to buy a given sound, a given set of similarities. In a club, they want to be entertained. To bridge that gap is a little more difficult than [that], it requires a Superman.

I started to say before that I at least find people now saying, “Gee, I’m glad that you do all of those things. I’d rather have you do all of those things than just be locked into a particular kind of thing.” Because to me, the song is the essence. Songs [that are] not good, I don’t care who does it. Doesn’t mean a thing. A song better be good. And that’s pretty much where it’s at. And those people who think that their particular styles and/or an arrangement are selling them are, I think, short lived. They better be able to go after and find the song constantly and/or perform the song. They must have the material.

Bobby on his first hits

(Interviewer) Back in 1958 when you did Splish Splash , where was your head then? What were you after? What were your goals at that point, when you started to really record professionally?

I wanted a hit record so bad I could taste it.

I don’t think I have told this to any anybody more than an intimate friend or two, but I don’t mind talking about it now. I had a rather severe case of psoriasis, which is a kind of a rash that breaks out on your hands. That’s usually triggered by some emotional disturbances. And I was being treated by a marvelous dermatologist in New York, and he would give me these ultraviolet treatments and cream. And after a long time, part of his treatment was to sit and discuss things. The treatment would only take 10 minutes. We’d shoot the breeze for 15 or 20. And one day he said to me, “when you have your first hit record, all this is going to go away.” Now, whether he planted that, or whether that was a fact that he had picked up on as a result of conversation, I don’t know. But I had recorded Splish Splash on a Monday, it released on a Thursday by the following Monday, we had sold 50,000 records, and it was just breaking all over the place. And by the following Thursday, my rash disappeared. You know, people out there could sit and laugh, and say “That’s funny.” That’s exactly what happened.

[Note by Shane Brown. This isn’t exactly how it happened. Splish Splash wasn’t released until five weeks after it had been recorded. It was recorded on April 10, 1958, and released on May 19th.]

So, I had such limited views, direction, such a narrow beam of light that I was looking through and traveling on, that the first hit record was an immediate. Then it was OK, now I’ve got to get the second one and the third one, the fourth one, and when I went in to do the That’s All album which had Mack the Knife in it, that was clearly and simply designed to show some people that I could do something else other than this rock and roll thing. Now, if somebody wants to get super analytical, they can say that’s because you were putting down the rock and roll thing. I don’t deny it. I was. But without knowing it. However, when they wanted to put Mack the Knife out as a single, I argued. I said, “don’t do that. You’ll hurt everything I’ve got going,” because, to me, I was like a man running on a treadmill and going nowhere. Inside I wasn’t going anyplace at all. I was starting to become the celebrity that I had wanted to become all my life.

Now, my attitude is very simple. I must do what artistically pleases me, and not worry about [what happens later].

And when you ask where was my head at in Splish Splash, that’s what sounded to me like it would be a hit record, and I went and did it. And Queen of the Hop sounded like it would be a hit record, and Dream Lover sounded like it would be a hit record…

(Interviewer) While we’re on Dream Lover, I want to point out that, to me, that stands out so far above [other pop hits]. I think it’s an excellent record from that period. Could you tell me a little something about the composition of that and the recording just for the heck of it? It was a very good record. I think it still is.

I had just discovered the C, A minor, F G seventh changes on the piano, and I stretched them out. And I liked that space that I left in there. And I don’t know why, because, as I say, I have no theory to base it on. And I did, “Every night, I hope and pray a dream lover…” And it just flowed because, usually, all of the songs that I’ve written that are hits have flowed out just like that. Whether I’m playing guitar and writing and/or piano and writing it, it just happens. That’s one of those cases in points. Splish Splash did as well. Then, to go in and record. I felt that should have some voices and some strings. So that was a little bigger date than I’d been used to doing. But, we did 32 takes on the song because we couldn’t get, in that particular afternoon we couldn’t get everybody to gel.

When I listen to the record today, I’m flattered that you say you think that out of that period, that was a good selection and I think it was a well-produced record…overproduced for today’s market. I think it’s a much more simple market today, put out a simple song with a simple idea that everybody could relate to. Again, though, I was going in to write for some people. I can’t say that I emotionally was divorced from looking for that love of my life, that would make me happy, and that’s what Dream Lover is all about. You’re the Reason I’m Living comes from it. But it comes from a definite need. An emotional need. And I think a thing like 18 Yellow Roses is a definite emotional need expressed in song.

Then I got a case of the cutes. And I started to write what I thought would sound like an emotional need, and things like Be Mad Little Girl – things that are so obscure and nobody even knows them, which is just as well. Now I’m back into writing things that I feel that I can relate to totally. And we’ll see what happens from there.

Bobby on the 1960s Music Scene

(Interviewer) I’d like to ask you, what do you think about the contemporary music scene now? What’s happening? Do you find it as exciting as I do and as everybody else seems to?

There is so much good music happening. So much. I mean, stimulating songs coming from stimulated songwriters being performed by stimulated artists that it really is a golden time. If you’ve got a capsule, a period of music, you may as well take the last couple or three years and really lock it up right there.

When you have a Lennon/McCartney combination, you have a John Sebastian, you have a John Phillips, Randy Newman, a Bob Dylan. You’re not talking about any lightweights, pal. And a Leslie Bricusse is the same, you know, coming into the same time era. You’re talking about giant strides forward musically, even though they are based on more simplistic ideas. They’re simplistic with involvement, simplistic with commitment.

True, there is nothing new, but the [key thing is the] way that today’s music is being presented. You take an Aretha Franklin. What a giant, what an absolute giant this girl is. Diana Ross and the Supremes, the entire Motown operation. Dylan, of course, has to be put very, very high on the list of major contributors. The Beatles. You know, somebody once said about Irving Berlin, they said, “well, outside of Irving Berlin, who’s the best songwriter?” Because it’s automatic, you know? Irving Berlin has contributed that much. Well, [now it’s] “outside of Lennon and McCartney,” because they have contributed [so much] in their short three or four years of success that they have to be separately categorized, separately positioned. They’re the triple A.

[Interviewer asks about how contemporary songwriters stand up to the likes of Rodgers and Hart.]

I think that if anybody wants to stack them up against Rodgers and Hart, that there’s a basic failing someplace. I think most people have a tendency to fondle yesterday and embrace it to the point of it being ludicrous. You know, I don’t want to make that comparison between Lennon and McCartney because I don’t think there is one to make. I think Rodgers and Hart served, and will continue to serve, a need on the part of the music appreciated by the music listener. Lennon and McCartney do just as much to serve a need on the part of the music listener and therefore the comparison ends where you say they write songs. There’s no need to compare them any more, so that there is a need to compare Woody Guthrie with Bobby Dylan. Now, the fact that there’s a bag to place Woody Guthrie and a bag to place Bobby Dylan in, that’s a shame that there has to be a bag to place them in. But if they’re right and they’re saying strong things, then that’s where it’s at for me, at least.

Link to the original source for the interview: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1703849/?fbclid=IwAR1mVtjJQunY-sKDAdJbMRRSlgQc3QlzffQ56G0TEPejwcAvzs6le-AjX0I

A speed-corrected version can be found here (with thanks to Alex Bird).

https://soundcloud.com/alexbirdofficial/bobby-darin-1967-interview-pitch-correction/s-E40HWMRicqF?utm_source=clipboard&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=social_sharing&fbclid=IwAR13mEXUHEkdVz_Vw7XJnNs37QO64M3GeclFAWvtPIIYafmFywOx0-D6Kpw